The Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM) is relatively nascent—the application of web3 technologies to transform the carbon landscape even younger still. Yet, there remains a pervading optimism about the market’s potential growth, as well as the use of blockchain in making it scale.

This brief summarizes the key drivers for the market’s growth and explains why it cannot be ignored. Overall, it shows that the VCM will be a central piece of the future net-zero global economy and that—like other markets before it, such as bonds and equity, the VCM will scale and be made more efficient through software infrastructure.

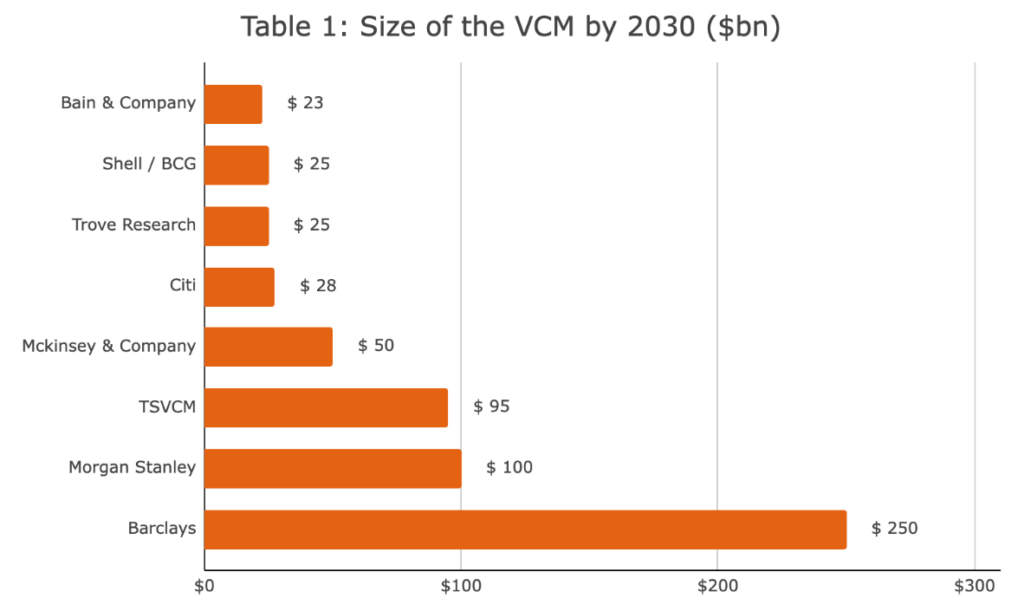

High-level voluntary carbon market estimates from independent analysts

The current size of the VCM is determined by the average price of credits transacted ($) multiplied by the number of credits retired (which serves as a proxy for demand).

In 2021, the size of the primary VCM reached $2bn. It, therefore, seems like a minnow – especially relative to the European carbon compliance market, which stands at approximately ~900 bn.

Exponential market growth is predicted in every forecast through 2030 and thereafter. As seen in Table 1, even the most conservative estimate sees the market grow to, at minimum, $15bn by 2030 (representing a CAGR of 35%).

Driver 1: Corporate Net-Zero and sustainability commitments

The biggest driver of demand in the carbon market will be from corporations, in particular those that have committed to net zero pathways and/or those who wish to make carbon neutrality claims. Pressure to commit to robust net-zero pathways currently comes at corporations from every angle – including investors, customers, partners & suppliers, employees, and—increasingly—governments.

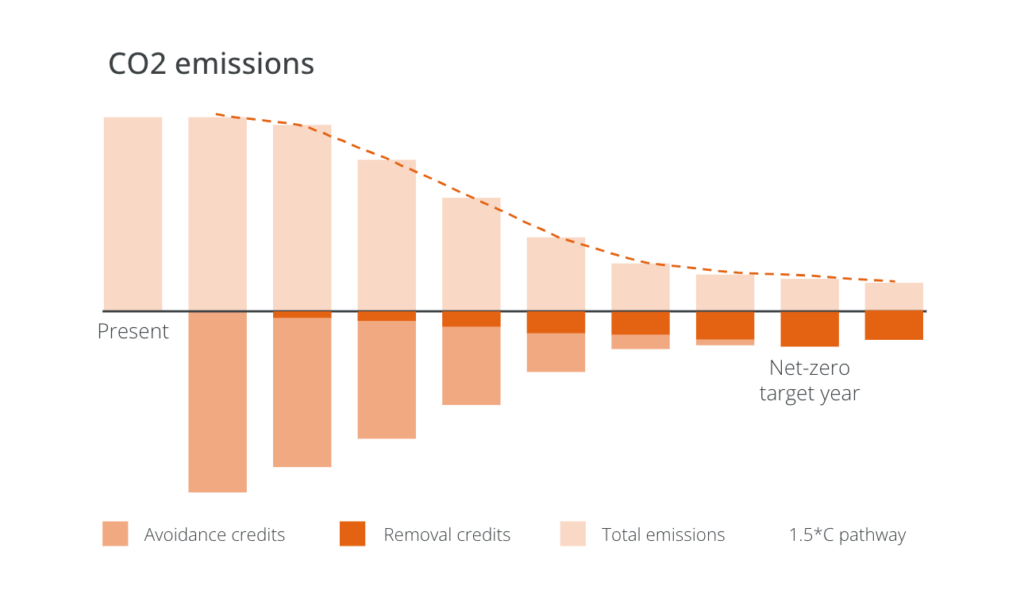

As seen in Diagram 2, net zero represents a critical balance between the emissions of greenhouse gases, particularly carbon dioxide, and the removal of these gases from the atmosphere. It is a pivotal step in mitigating the effects of climate change and limiting global warming.

Although such pathways are—for now—non-binding, they ‘bake in’ future demand for the carbon market because of the need to compensate for residual and/or un-abatable emissions. Moreover, because of increasing marginal abatement costs (read: it gets harder to decarbonize as you get closer to net zero), robust carbon offsetting is central to de-risk net-zero pathways. This is particularly true for the most carbon-intensive and hard-to-abate industries (a good example is Rio Tinto).

The following statistics give a sense of the scale of net zero commitments by corporations and finance:

- 66% of the annual revenue of the world’s largest 2,000 companies (equivalent to $27 trillion) is now covered by a net zero target – representing a 40% YOY increase between October 2022-2023 (Net Zero Tracker).

- 79% of large corporations have climate targets and 89% of these turn to carbon credits for emissions they cannot yet eliminate (Conservation International).

- 66% of large corporates rely on carbon offsets as part of their Net Zero target (Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment)

- The Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative currently has over 315 asset manager signatories with over $64 trillion in AUM (Net Zero Asset Managers)

- 8 of the 10 world’s most valuable brands already use carbon credits, or have pledged to do so, including all of the top 4 (Amazon, Apple, Google, and Microsoft)

A quick mental calculation to put things into perspective:

To stay on track for 1.5C (as per the Paris Agreement), annual emissions need to fall from around 36.8 billion tonnes (on fossil fuels alone) to 20 billion tonnes by 2030.

Assuming high-integrity offsets need to do 20% of that heavy lifting, which is a very conservative estimate

Assuming we actually also achieve an 80% reduction-by-direct-decarbonisation goal (a big assumption) then the annual need for offsets declines year-on-year as emissions decline.

That gets the VCM to a cumulative growth of 384% over the next 7 years.

Driver 2: Emergence of retail carbon credit markets

One area of huge potential in the VCM—that has until now remained untapped—is the consumer market. Here, most market analyses forecast that carbon offsets will increasingly be embedded in many purchasing decisions that retail consumers make each day. Deloitte predicts consumer purchases of carbon offsets will become pervasive and grow into a nearly US$100 billion market in developed economies by 2030 (Deloitte).

New carbon-trading networks emerge that cater to the heightened demand for tailored, localised, and niche actions to help mitigate climate change. This growing vertical will depend upon strong digital infrastructure – Thallo is building this infrastructure.

More payments firms are empowering consumers to reduce their carbon footprint as well. The digitization of carbon-market infrastructure, such as the one being built by Thallo, could make it easier for carbon credits to be divvied up and sold on mobile apps, payment transfer systems, and as embedded-finance functionalities on user platforms. For example, Visa allows banks in the Asia-Pacific region to enrol in Eco Benefits, which calculates the carbon footprint of transactions for consumers and allows them to counterbalance emissions in a mobile app (Visa).

Similarly, residential real estate businesses should be heavily engaged in carbon markets because their clients increasingly demand carbon-neutral properties. As of 2019, the real estate industry accounted for 38% of greenhouse gas emissions. In addition to new legal requirements and net-zero obligations, consumer demand should also bring about more demand for carbon credits. Many tenants would pay more for premium accommodations, including buildings certified as carbon neutral (JLL).

There is already lots of evidence of this growing appetite:

- More than 50 global airlines now offer carbon offsetting to passengers (CNA).

- Carbon Checkout, a one-click offsetting application co-funded by the European Innovation Council of the European Union, has formed over 2,000 e-commerce partnerships since launching in 2015 (Carbon Checkout)

- Two-thirds of US consumers say they would pay more at the pump for gas that offsets its greenhouse gas emissions (PDI Technologies)

- Despite the surge of inflation in 2022, the market for sustainable products accounted for 17.3% of purchases in the United States last year (NYU Stern)

- An international survey last year found that two-fifths of consumers say they would pay a higher price for climate-focused products (Shopify)

This demand for retail-based offsetting will likely only grow as younger people, who often prefer sustainable products, gain purchasing power (Deloitte).

Driver 3: Regulation and linkage with compliance markets

Governments worldwide now recognise that market instruments are central to global decarbonization and achieving a country’s Nationally Determined Contribution (per the Paris Agreement). The carbon market is an essential legislative tool for governments to bridge the gap between climate ambitions and policy actions. Two carbon-specific policy instruments are available to governments: 1) a carbon tax and 2) an emissions trading scheme (ETS).

Explainer: Carbon Pricing Instruments

A carbon tax directly sets a price on carbon by defining an explicit tax rate on GHG emissions – or, more commonly – on the carbon content of fossil fuels, i.e a price per tCO2e. The carbon price is pre-defined.

An emissions trading system (ETS) is where emitters can trade emission units to meet their emissions targets. Regulated entities can either implement internal abatement measures or acquire emissions units in the carbon market, depending on the relative cost of these options (they often deploy a mix of both). Two main types, cap-and-trade and baseline-and-credit. The emission reduction outcome is pre-defined.

As of October 2023, there were 47 National and 36 Subnational carbon pricing schemes. In total, 23% of the world’s Global Greenhouse Gases are covered by one of the carbon pricing schemes.

Importantly, the line between compliance and voluntary carbon markets is becoming increasingly blurred, particularly through jurisdictional regulations and tax incentives.

For example, Singapore has recently set its eligibility criteria for carbon credits that can be used to offset its carbon tax. It joins a growing number of other countries, including Colombia, Chile, and South Africa, that are building similar tax regimes. Given that the size of just the EU compliance market is $900 bn, tax incentives that bridge the voluntary and compliance markets will prove to be an enormous driver of demand in the VCM.

Other regulation and fiscal incentives will also play a key role. For example, the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which taxes heavily polluting imports, is likely to be a growth driver long before it comes fully into effect in 2026.

Here, if an importer can show that a price has already been paid for the carbon emitted, it would not need to pay the tax when importing into the EU. In effect, the CBAM will drive up the prices of carbon in non-EU national and regional compliance markets in order to ‘level the playing field’ and avoid paying EU levies. This is just as true for Australia, where there is no national carbon price, as Singapore, which has a lower carbon price and a mechanism for using voluntary carbon credits to offset their compliance tax burden.

Driver 4: Article 6 and improved quality standards for carbon offsets

Another major shift underway in the market is clarification and agreement on the rules and quality standards pertaining to offsets. This will prove pivotal for an industry that has long been beleaguered with accusations of housing low-quality and cheap credits that fuel greenwashing.

Two changes are most notable: 1) clarification on the rules of engagement around Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, and 2) emerging market standards on what quality means (both on the demand- and supply-side of the market)

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement creates a common rulebook for what can qualify as a carbon credit (i.e., by restricting the criteria) and how it can be used for different purposes (i.e., by addressing double counting concerns). For nations, this means increasing the flow of climate financing, particularly for developing countries most in need.

With finalization of Article 6, expected this year at COP, voluntary markets could see substantial change, which would drive increasing demand from the private sector and investments in supply.

Separately, two initiatives have come into implementation in 2023 that could prove game-changers for improving quality and standards in the market: the IC-VCM’s Core Carbon Principles and the Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative’s Claims Code of Practice.

The IC-VCM’s Core Carbon Principles (CCPs) focus on supply-side quality and aim to usher in high-quality across the voluntary carbon market. The CCPs will set a global standard for high-integrity carbon credits based on clear and verifiable data. Credits that meet the CCP criteria will be labeled and recognized as high-quality. The CCP label will identify carbon credits that meet the high environmental, social, and climate integrity criteria set out in the CCPs. The composability of blockchain is increasingly recognised as a means of disseminating the usage of CCP labels across the industry.

The VCMI Code of Practice, on the other hand, focuses on demand and provides corporate offtakers with a rulebook on credible use of high-quality carbon credits, and associated climate claims, that will accelerate climate action. This aims to build a broad sense of trust and confidence in how companies engage with VCMs. This, combined with better digital infrastructure that enables corporations to monitor, disclose and manage their carbon strategies (such as Thallo’s), will be important in clarifying the ‘rules of engagement’ for corporations.

Ultimately, these developments will fuel demand for high-quality carbon credits, which in turn will lift prices in the voluntary carbon markets.

Driver 5: Reduced evidence of greenwashing

Multiple research efforts have found that companies that purchase material amounts of carbon emissions actually decarbonize nearly 2x faster than companies that do not – a strong argument against greenwashing.

But then the question remains: are carbon credits necessary? While experts disagree about which carbon credits are best, nearly every serious climate player recognizes the need for both major cuts in carbon emissions and removal of carbon already in the atmosphere. And carbon markets remain one of the few non-philanthropic mechanisms to move real capital to these solutions.

IPCC research shows that the top 5 levers to meet the global carbon budget are all areas that carbon credits address: renewables, reducing destruction of natural ecosystems, sequestration in agriculture, and ecosystem restoration. Separate IPCC research shows humans must remove carbon – going beyond net zero – to reach the Paris Agreement aims.

As such, the growing evidence that the use of high-integrity carbon credits actually furthers genuine climate action, combined with digital infrastructure and tools that allow corporations to better manage their carbon accounting and offsetting strategies (like EY’s Ops Chain ESG tool – with planned integration into Thallo’s API), the VCM’s association with greenwashing is likely to become something of the past.

Carbon Market FAQs

1. What are the leading market trends in the carbon market?

The carbon market is increasing and is expected to reach significant levels by 2022 to 2030. This is driven by the growing demand for carbon credits and emissions reduction initiatives to achieve net-zero targets established under Article 6 of The Paris Agreement.

2. What are carbon credits?

Carbon credits represent a reduction or removal of one ton of carbon dioxide or an equivalent amount of other greenhouse gasses from the atmosphere, which can be traded in the carbon market to help companies meet their emission reduction targets.

3. What is the difference between voluntary and compliance carbon markets?

The voluntary carbon market consists of companies and individuals voluntarily purchasing carbon credits to offset their emissions, while the compliance market involves companies complying with government-mandated emission reduction targets by trading emission allowances and carbon credits.

4. How does a carbon offset work?

A carbon offset is a reduction in emissions of carbon dioxide or other greenhouse gasses made to compensate for emissions elsewhere, and it is achieved through projects such as renewable energy, deforestation reduction, and emissions reduction initiatives.

5. How does the carbon trading system contribute to decarbonization?

The carbon trading system incentivizes companies to invest in sustainability and renewable energy projects, reducing emissions.