Intro

I have been an investor, builder and advocate of Web3 since the initial release of the world computer, way back in 2015. In my experience, one of the many clear value-adds that Web3 offers over traditional models is that any successful, long-term model must be self-sustaining. This forces network designs to be additive to all beneficial network participants, ensuring actors within the network are encouraged to remain honest and contribute to the efficient running of the system. We call this incentive design.

Along with an exceptional founding team, I helped create Thallo early last year. My recent career had been in no small part around designing incentives in order to ensure innovations in the market became self-sustaining over time. What quickly became evident to me, is that our current incentive model — humanity’s model — is far from self-sustaining.

Our model of global debt creation in modern society has ushered in an age of incredible innovation, of exponential increases in the quality of life of humanity around the globe. That much is irrefutable. Debt creation as a network effect is inherently beneficial, even if some second-order effects are largely negative. We incentivise innovations in healthcare, food creation, transport, communication, and more — all through the creation of debt and monetary stimulus.

But money is not currency. Money is a medium of exchange, an item or verifiable record that is accepted as payment for goods. Currency is often nation-specific, accepted as a vehicle of debt.

Currency is a blunt instrument for recording debts.

Money is humanity’s single greatest invention in that it crosses borders of nation states, of cultural or religious practices, of human behaviours.

Therefore money, by definition, is humanity’s greatest tool to align incentives and disincentivise non-beneficial actors, or at the very least rewrite the features of money to incentivise sustainable practices.

Clean Money & Carbon Markets

MakerDAO’s Rune Christensen talks about The Case for Clean Money, whilst Celo intends to collateralise up to 40% of their stablecoin reserve with natural assets over the next 4 years.

Arguably these ideas gave birth to the burgeoning Regenerative Finance (ReFi) movement, and whilst these ideas are lucid, inspiring and mission-driven, the underlying ideas are not new. Carbon Markets have existed in some form since the Kyoto Protocol, but it was the treaty that really drove considerable investment into Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions reduction projects worldwide.

The protocol established a global emissions trading system, establishing buyers — developed countries using money to incentivise lower emissions — and sellers — generally developing countries incentivised to develop projects with either a primary or secondary result that included the reduction of GHG.

The underlying idea was to incentivise developing countries, who desperately needed money for development and growth, to earn that income from developed countries, who in turn were content to provide investment for projects that reduced GHG emissions, and therefore reduce future environmental risk for their citizens. It was a beautiful alignment of incentives.

We then saw the establishment of the Voluntary Carbon Markets (VCM), whereby organisations and businesses began offsetting some of their emissions through an analogous, but initially much smaller in scale, market structure.

The early success of the VCM was short lived with traded value plunging 47% in 2009 largely because of the recession — a period of economic decline and in itself a stark example of what happens when incentives are wrongly aligned to profit a subset of a community.

Capitalism intervened, as often happens when the need arises, but the VCM struggled to catch up and continued to decline until 2017 at which point traded value had fallen to below 20% of its peak almost 10 years earlier. Sellers outnumbered buyers, and as supply/demand economics dictates, the prices were low, and incentive to create quality, verifiable credits was equally absent.

Recently, and certainly within the last 12 months, this dynamic inverted. Volume doubled last year, and demand has begun to outstrip supply. This fact is critical to the rest of the article, so take note.

Voluntary Carbon

Voluntary carbon markets suffer from some drawbacks. They are unregulated, quality controls often act as a bottleneck to increasing supply, and like any unregulated market, nefarious actors must be combatted. But in truth, it is the only carbon market vertical with global reach.

I recently read an article by venture capitalist and entrepreneur Ben Casnocha, about what he’d learned from spending over 10,000 hours with legendary entrepreneur Reid Hoffman. There is a lot of alpha in there, but one point stuck with me, and I wasn’t immediately sure why. Yesterday, it hit me like a brick:

“Most strengths have corresponding weaknesses. If you try to manage or mitigate a given weakness, you might also eliminate the corresponding strength.”

The very fact that the VCM is unregulated is its weakness as well as its strength. If a single entity attempts to regulate the market, control quality, or dominate supply, then we must submit to the whims of that entity in each of those areas. We must allow the market, and the actors therein, to establish quality controls and regulations that retain the VCM’s global remit.

Incentive structures are what truly determine the efficiency of any market. When those incentives are aligned, any actions in the market are positive-sum, regardless of actor.

So far we understand an abridged version of the origin of carbon markets. We understand that the VCM is nascent, and growing exponentially. We even understand that the markets are not currently perfect, and that such a fact is, in and of itself, a positive of sorts. But let’s dive a bit deeper and understand a metric that is critical to the future success of the carbon market: project quality, and how quality is critical for the alignment of incentives.

Whilst quality in the market is subjective, it is an indisputable fact that not every carbon credit is the same (more on this below). For instance, some projects will avoid, reduce or remove carbon more permanently than others.

A classic example is a forestry project. Trees are planted — or at least not cut down or removed — and the resulting growth of those forests reduces CO2 emissions. Now imagine the same forest suffers from a forest fire. The CO2 is re-emitted into the atmosphere, and a reversal occurs. Paradoxically, as the climate emergency becomes more desperate, this method of CO2 removal becomes less permanent, as global temperatures continue to break records and more forest fires are expected.

On the other hand, carbon removal technology such as Direct Air Capture (DAC) is considered by some to be far more permanent. CO2 is captured chemically in a concentrated fashion, and then stored deep underground, where a reversal is much less likely.

Some projects may also deploy developmental ‘co-benefits’. An example of a co-benefit might be a climate mitigation technology that also reduces air pollution in cities, the co-benefit being human health and sustainable cities.

Consider also the example above, where the planting of trees increases biodiversity, reduces soil erosion, and can also increase air and water quality.

Renewable energy projects can lead to reduced energy imports, local community employment, reduced poverty, economic growth, and even gender equality through creation of jobs.

The United Nations member states also adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to measure co-benefits. A success story comes from household cooking stoves provided to families in South Asia. Much of the cooking in countries such as India & Pakistan is done by women. Traditionally, they will collect wood for fuel, and then proceed to cook indoors without adequate ventilation.

Efficient fuel stoves were provided to these families, which in turn generated carbon credits. But the real success comes from the number of SDGs that such an initiative supported:

- No Poverty

- Good Health

- Gender Equality

- Affordable & Clean Energy

- Work & Economic Growth

- Climate Action

- Life on Land

So what does all this mean? In essence, carbon markets are complex. Co-benefits, additionality, leakage, reversal, permanence and other topics key to understanding the market — all combine to mean that solutions to the climate emergency are far from simple.

They point to complex differences in demand, as well as supply. For example, multinationals are often interested in only purchasing the highest quality credits. The cost-saving benefit of purchasing low-quality and therefore low-cost credits is not worth the loss of custom that may occur as a result, as more of their users begin to understand the complexities and what quality means in the market.

Corporates are often keen to establish ESG & CSR policies that conform to their intended reputation in the market, and thus their voluntary purchasing must follow these internal guidelines.

Retail purchasers may wish to support local projects, for example, a Pakistani wishing to offset carbon generated from a trip may elect to support the cookstove project described above.

Which brings me to my next point. Where are we currently in establishing ReFi as a foundational model for clean money?

The Current State of ReFi

The current model in ReFi is exclusively a model of commoditisation. Projects which begin as individual, distinguishable projects with attributes that conform to and appeal to company CSR policies or personal preferences are lumped together into a single pool (or a number of pools).

The reason for this comes down to liquidity, and fungibility. When carbon projects are highly unique, they are by definition not fungible. A lack of fungibility often precedes a lack of liquidity in markets. And a lack of liquidity means a non-functioning market.

So the (simple) solution is to commoditise carbon credits. You buy a carbon credit, rather than the carbon credit. This solves the liquidity problem, by and large. With a giant pool filled with nondescript credits, you are able to just sell a tokenised share of the wider pool.

Enter KlimaDAO. I am of the firm belief that the Klima founding team’s intentions were pure, and that they have an intelligent (albeit anonymous) team that have bought a considerable amount of progress and created a large, like-minded community of individuals to the ReFi space. I feel blessed to be part of a space and community with such trailblazing entities as Celo, MakerDAO, Klima, Toucan, and other ReFi projects.

But KlimaDAO could not, or did not, consider second-order effects. On first principles, the project was technically sound:

- Introduce a ‘carbon black hole’, backed by experimental economics and game-theory tokenomics originally pioneered by OlympusDAO.

- Provide liquidity to the on-chain carbon markets in the form of a commoditised pool.

- Lean on a fundamental principle in carbon accounting: the higher the price of (offsetting) carbon; the more it costs governments and companies to partake; the more economically feasible it becomes for these entities to instead invest in carbon-reduction and removal projects of their own. Long term reductions in their own emissions will cost less over time than continuous purchasing of carbon credits.

- KLIMA — the currency introduced by KlimaDAO in exchange for the deposit of carbon credits — then becomes a carbon market index of sorts.

- A recent poll of 30 climate economists suggested that in order to reach the Paris Agreement’s goal of net-zero emissions by 2050, we must increase the average price of carbon credits from $3 (the current) to $100 per ton of CO2.

- Klima’s logic was simple. ‘Sweep the floor’ by buying the cheapest credits on the market, and removing them from circulating supply (locking it into the carbon black-hole). As the floor price increases, and less credits are circulating, simple supply-demand economics will increase the price of an average carbon credit.

On the face of it, this logic is sound and initially worked to great effect. The price of KLIMA shot up to almost $4,000. Staking returns were enormous, if unsustainable. The carbon black hole has genuinely absorbed an incredible amount of credits — over 20 million tonnes.

Since then, KlimaDAO has fallen from grace somewhat. The price of KLIMA has tumbled from $4,000 to less than $20 at the time of publishing.

The subsequent fall can be somewhat attributed to the economics of OlympusDAO (and offshoots such as KlimaDAO) being unsustainable in their current form, but there is further criticism.

KlimaDAO is led by an anonymous team. This isn’t necessarily an unusual model for a Web3 DAO, which by definition is intended to be both decentralised, and autonomous. This is much harder to accomplish with known entities acting as figureheads, and to be clear, I personally believe DAOs to be a highly interesting experimental, meritocratic model that may well have its place in future society.

But asking contemporary multinational companies and non-Web3 retailers to trust — and participate in — organisations that do not have identifiable founders is a non-starter for global reach.

Then there are second-order effects. Whilst on the face of it, the ‘sweeping the floor method’ should have led to an increase in the average $ price of a carbon ton. Instead, it led to an arbitrage opportunity as the price of BCT increased beyond the floor price of credits that were introduced to the pool. These credits were in some cases widely determined to have used fraudulent accounting to create the credits, or were even cited as Zombie Projects by Carbonplan.

Essentially, these were projects that were bridged to Klima’s black hole that had no buy demand pre-Klima. Traders were arbitraging parts of the market such as VCS494, which prior to Klima, had a last recorded retirement date of April 30, 2013.

Another project currently residing in Klima’s black hole, VCS191, had zero retirements prior to this arbitrage opportunity.

Klima users were buying credits that had no addressable market, therefore somewhat mitigating their “sweep the floor” tactic.

Here is where the current ReFi market falls short. By commoditising an entire market, and removing any individuality (additionality, co-benefits) from the origin projects to place the credits in a single pool, the pool will always attract the lowest-quality credits as this becomes the most profitable model for participants. Not only this, but arguably this incentive mechanism now increases the demand for low-quality credits.

If there is constant demand for the lowest quality credits, then supply of a similar low quality will increase to match the demand. KlimaDAO’s model, whilst on the face of things noble and good-intentioned, is arguably increasing the demand for the exact credits they are looking to remove from the market.

Let me be clear that this article is not intended to be an assassination of Klima’s model or their intentions. At the heart of it, they (and their community) are innovators, and we desperately need innovation to solve the climate emergency. At Thallo, we very much stand on the shoulders of giants in the ReFi space — but like any innovation, improvement must be constant. We believe that we are the next iteration of ReFi. Let me explain why.

A new model for ReFi

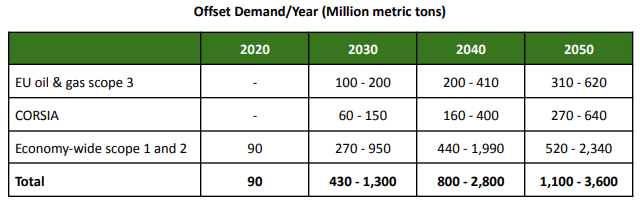

We believe the VCM will have an extremely wide audience, and will grow to orders of magnitude larger than its current capabilities, in terms of both supply and demand. In many ways, this is already occurring. Offset demand from pre-2005 to mid-2021 cumulatively was 1.728 billion tons.

Credit demand in voluntary markets by 2030 has been estimated to almost reach this entire cumulative total per year. By 2050, it may treble that figure annually.

A market with such a high level of demand-side interest will have an extremely diverse set of requirements based on industry standards, individual preference and CSR/ESG goals.

Therefore, Thallo’s product suite will ensure that project characteristics, the defining properties of each carbon credit, will be retained on chain. Each credit will be traceable to the project that it was borne from, and be filterable and searchable by its unique properties.

This will allow the creation of portfolios of carbon credits on the VCM that are less sensitive to price fluctuations in the market, as trading of various pools of SDGs; vintages; geographical origins; etc encourages portfolio diversification and further establishes carbon as an on-chain investment.

In the words of Mars Garza, we are “working with carbon projects versus carbon credits” (emphasis added).

The Thallo team also believes in transparency throughout. Transparency throughout the market to avoid double accounting and the like, but also transparency in the team, our funders, our vision, and our techniques.

We also believe in taking a registry-first approach to bridging credits. Registries such as Gold Standard and Verra, as well as more boutique outfits, are driving standards to ensure high quality credits within the market. The watermarks of the aforementioned registries are assurances of quality Measurement, Reporting, and Verification (MRV).

Thallo is working towards two-way bridges with each of these entities, allowing credits to move on and off-chain as liquidity requires, effortlessly.

This model may adapt as the market matures, towards data models driven by Web3 ecosystems such as dClimate or OFP.

Thallo is aiming to partner with an abundance of supporting entities and protocols to ensure the highest standards for the VCM now and in the future.

Align incentives, save the world

What is ReFi’s ultimate goal? Arguably, it is to create new financial instruments that utilise and increase demand for green assets such as carbon credits, and in the long-term, to make viable an entirely new economic model built on regenerative financial assets.

What are our near-term challenges? As previously explained, we need to ensure we do more to educate participants about the quality of carbon credits, and their properties inherited directly from the project source. We must drive standards on-chain utilising off-chain partners such as registries, ratings agencies, and data providers/aggregators. And we must understand that a supply crunch is coming.

I mentioned earlier in the article that until now, supply of carbon credits was plentiful. This model is now inverting, and the demand for credits in the VCM is quickly outstripping supply.

This is already true with billions of dollars in demand yet (or just beginning) to enter the market with the invention of ReFi, through partners such as Celo, or MakerDAO. This is before the creation of new on-chain instruments utilising carbon credits, such as futures contracts, Carbon Purchase Agreements (CPAs), carbon credit indexes, carbon project bonds, and more. Clearly, demand is going to quickly outstrip supply. Supply-demand economics dictate that the average price of credits will increase as this continues to play out, which was our goal all along, right?

But let us again revisit second-order effects. As prices increase, projects of lesser quality are easier to deploy for quick profits, taking advantage of the average price increase of the market. Therefore ReFi, and the wider carbon market in general, must incentivise supply. But it must incentivise supply to exponentially increase production of high-quality credits.

I would like to leave you with an example as a thought exercise, a model which Thallo will explore further in the coming months as we deploy to production.

Removing supply from the market (IE — retiring credits) is a primary reason for the existence of the VCM. But in considering an alternative use for credits, as collateral for financial instruments or as assets to trade, retirement is not immediately conducive. Ultimately, retirements are a legitimate tool within the VCM toolbox, but the overarching goal is to increase the quality, and the number, of CO2-reducing projects throughout the globe.

I posit that trading, speculation, and increased deployment of quality credits to collateralise financial instruments, are all much more likely to contribute to our end goal.

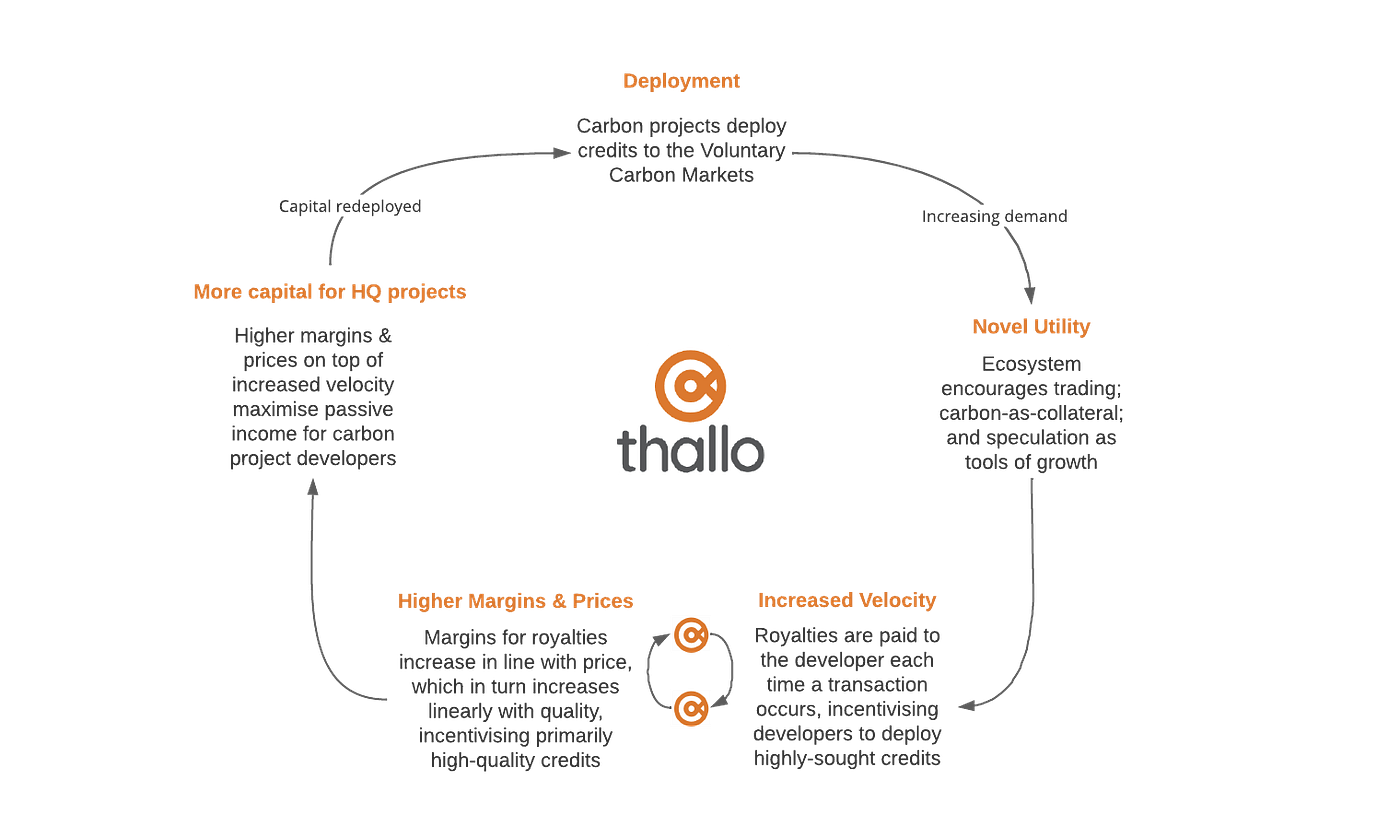

Summarised in the graphic below, the journey is as follows:

- As ReFi envisions more use for Carbon Credits as a financial primitive, and novel utilities for credits increase on-chain, growth in demand will undoubtedly occur.

- As trading is enabled on the Thallo platform, and demand for credits increases in line with utility, velocity of trading will increase in turn.

- Prices are likely to increase for the highest-quality carbon credits as velocity and demand for such credits increase.

- A royalty model is applied throughout. Each time a trade is made in the Thallo ecosystem, a transaction fee is enforced, and a portion of that transaction fee is fed back to the original project developer.

- As royalties increase, project developers earn increasing amounts of passive income.

- The passive income is used by developers to deploy more capital to projects. Passive income increases with velocity, utility, and crucially — higher margins for high-quality, therefore premium-priced, projects.

- The cycle begins anew, but each time developers have increasing amounts of capital to deploy, with an incentive to create higher-quality credits as demand dictates.

The above model will eventually establish a self-sustaining price-point of passive income, capital redeployment, and increasing supply, which leads to an ever-increasing removal of CO2 with quality at the forefront.

Iteration

Iteration is key to innovation. The above model is but one of many that Thallo is currently considering, and we will only know which workflows or models are successful with community feedback, collecting results, and iteration.

Some of the brightest minds in both Web3 and Sustainability are currently working in this nexus. I implore these minds to offer criticisms and improvements to this article, and ecosystem design.

Together we will find the right incentives as the space progresses to align actors and exponentially increase the CO2 removal capabilities of the market. Carbon Credits are but one solution in the sustainability sphere, but in my mind —a solution which can become money, which since time immemorial has been a primary driver of human progress.

Please reach out with feedback on @thallo_io, to me directly at @regenfi.eth, or join our Telegram.